Windrush and a deeper Caribbean legacy - Part II

![British newspapers at the time of the Windrush arrival [photo: Debbie Ransome]](/sites/default/files/page/British%20papers%20on%20Windrush%20arrivals%20web%20large%20British%20Library%20photo%20by%20Debbie%20Ransome.jpg)

By Debbie Ransome

As the mainstream stories about the NHS and London Transport will tell you, post-war Britain did need nurses and transport workers. Outside the BBC World Service (see part one of this article), doors were not so readily open to the Caribbean’s educated classes who had served in the war and then returned to the UK.

As part one of this article indicated, the 1948 arrival of Windrush was not the start of multi-racial Britain. Many Caribbean people had been serving in the RAF, other parts of the armed forces, at the BBC or had been studying in the UK. Their sea voyage in the late1940s had been a return for them, with wartime ties and education being the main motivation for travel from the British West Indies to the UK.

The narrative of the educated West Indian seeking a life in post-war Britain is best documented in E. R. Braithwaite’s book “To Sir, With Love”. The Guyanese-born son of Oxford-educated parents, Braithwaite left Cambridge to find that work was not available to him in his field, forcing him to take up teaching in the East End of London. The experience, of course, led to his seminal book and the even more famous film version starring Sidney Poitier.

London is the place...

In terms of musical contributions, Windrush was also the global launchpad for Trinidad calypsonian Lord Kitchener (Aldwyn Roberts). Lord Kitchener, known as “Kitch” back home, was encouraged by Pathé to perform some of the lines of his newly-composed “London is the place for me” in the now famous film reel of the Windrush arrival.

Kitch was already famous on the other side of the Atlantic. He had performed in 1945 before US President Harry S Truman and had a string of calypso hits in Trinidad. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography said that Kitch “provided white audiences with one of their first images not just of calypso music but also of the cultural implications of post-war immigration policy. Soon afterwards, Kitchener's songs began to introduce these audiences to aspects of a Caribbean culture that was now taking root in England.”

Kitch returned to Trinidad in 1962 for a long and honoured career while, for many in Britain, he remained the black-and-white introductory image to the world of calypso.

While it’s easy to take a rosy view of the Windrush arrival and its legacy, the downside of such numbers arriving was hard to ignore, even while the British press celebrated the arrival of new and much-needed workers. The British newspapers of the time indicate the mixed reaction: both of welcome, for the numbers to boost Britain’s post-war efforts, and of alarm at the continuing growth of arrivals.

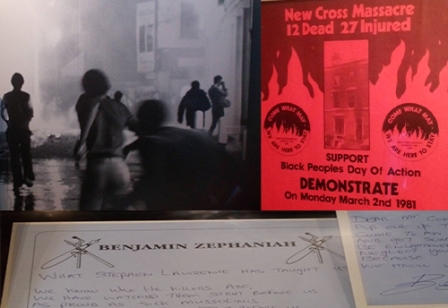

Photo exhibitions and other events in June 2018 have focused also on the decades of racism and upheaval that the new Diaspora faced.

From the “no Blacks, no Irish” signs outside 1950s boarding houses to the riots of the 1970s, and more recently, the murder of Stephen Lawrence and today’s Windrush scandal over the immigration status of many people who arrived in the UK before 1973, the growing pains of a Caribbean Diaspora in the UK have not been easy and many of the articles and exhibitions have sought to portray this at #Windrush70.

Windrush scandal

There had, of course, been a Caribbean presence in the UK before the war. June 2018 has become a focal point for annual celebrations of the contribution of West Indian people living and working in Britain and focusing on the contributions of today’s Caribbean Diaspora.

Today’s politicians continue to argue over the Windrush scandal and the compensation promised by government for those treated badly under Home Office migration policies of the last few years.

It seemed in June that every time the Windrush scandal disappeared from the front page headlines, another series of media reports appeared, probing the experiences of the Windrush generation.

One of those people who became a voice for that generation and their children in the 1960s, 70s and 80s is Grenadian-born Alex Pascall, OBE. He travelled to Britain in 1959 and worked as a former producer with the BBC’s Caribbean Section in the 1970s, then as the long-term presenter of BBC Radio London’s Black Londoners programme in the 70s and 80s.

What did he think of the June 2018 parade of events?

“As Caribbeans, we are a generation of many whose contributions goes beyond the recognition afforded to us by British governments,” Pascall told Caribbean Intelligence©.

“Nevertheless, we have over the decades and within the 20th Century, awakened others to who we are and why we are citizens of Britain, not immigrants nor ‘low-hanging fruits', but a people of many cultures who, in our strides, have fortified Britain's economic advancement and brought change to the dull shores.

“We remain resilient and watchful, knowledgeable and steadfast to the fact that educationally and artistically we have made enormous strides and, in so doing, cultivated this amazing festival of natural innovation: The Notting Hill Carnival, the place where all meet to celebrate in harmony; peoples of colours, cultures, creeds and races together, regardless of class.

“We have, with time, done more than community relations have managed and the government knows it well. The SS Windrush and its arrival is only symbolic, we came long before the ship in journeys across the Atlantic. Those of us here today and generations before are the products that now fortify this nation in establishing itself as the United Kingdom.”

The current generation are not short of online and teaching material giving them a sense of the Windrush experience – from 2018 special exhibitions to online teaching resources. One excellent teaching pack, entitled Bound for Britain, from Britain’s National Archives aims to take young people through the experience of the Windrush generation’s arrivals and their early days in Britain.

It’s clear that much of this year’s teaching and exhibition material is pitched at all children, even those of Caribbean origin who are now three, four and five generations away from their West Indian roots.

As this range of experiences were being celebrated, probed and shared throughout June and the rest of 2018, the 22nd of June and the ship that arrived that day at Tilbury Docks in 1948 have become a marker for the contribution of a people, many of whom had only come for a short time to help out and to seek opportunities in “the Motherland”.

Related articles

Part one - Windrush and a deeper Caribbean legacy

Windrush – Who exactly was on board? BBC News

Writing the Windrush – a critical thesis

Windrush generation's resilience hailed at Westminster Abbey anniversary service – Huffington Post

Alex Pascall’s Good Vibes Records and Music Ltd