Resilience: How the Caribbean helped create a global benchmark

By Debbie Ransome

It was a disaster for the Caribbean, but a lesson learnt for the global community. The year that saw the most costly hurricanes – 2017 – raised more calls from small states in the Commonwealth for better ways to measure a nation’s ability to bounce back following catastrophes.

As it turned out, the growing frequency and intensity of hurricanes in the Caribbean and increased storm devastation in the Pacific laid the basis for a new measure of resilience and vulnerability which the Commonwealth is offering the wider world. In 2018, Commonwealth foreign ministers asked the organisation’s Secretariat in London to design a new way to link vulnerability and resilience and provide a more flexible and nuanced approach to measuring aid, concessional loans and other forms of support following a disaster.

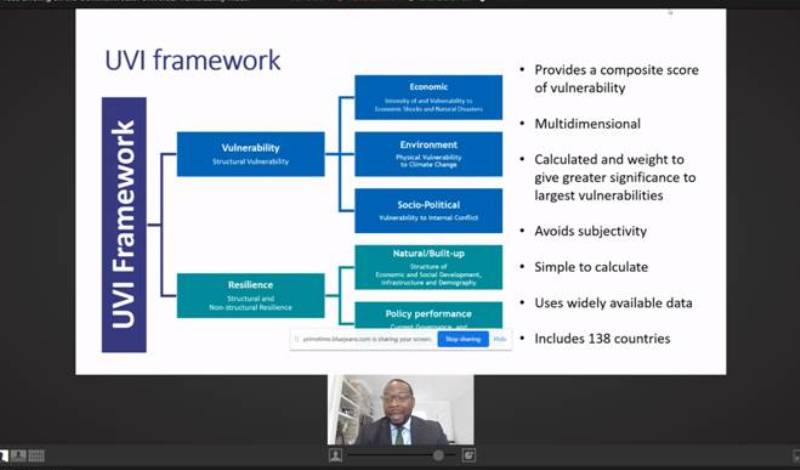

The result is the Universal Vulnerability Index (UVI), unveiled by the Commonwealth Secretariat on 24 June. The UVI was drafted in April 2021, in time for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in June, but got a separate launch after CHOGM was again postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The UVI fuses measurements of what makes a country vulnerable (its environment, economic status and socio-political rating) with what makes it resilient (its infrastructure and its policy performance). If you chart this on a sliding scale, you can start to measure the elements within and outside of a country’s control. You also have a measurement for the level of aid and other support needed to build back better.

Commonwealth officials hope this measure will replace the use of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the current baseline for funding – which penalises middle-income countries hit by disaster. They plan to take the UVI proposal to the G20 and other multilateral groups for adoption as a benchmark, based on more flexible but vigorous analysis by countries and financiers.

“This [GDP] doesn’t work any more and we need to have a real change on how we deal with vulnerability,” Dominica-born Commonwealth Secretary-General Patricia Scotland told the June media briefing held to launch the UVI. “It’s not the best measure of a nation,” she said, adding that UVI had arrived at just the right time, as it addressed the realities of climate change.

‘Nuanced and constructive’

Baroness Scotland said the usefulness of GDP as a benchmark of a country’s vulnerability was “waning” as the world becomes more complicated. She pointed to the use of big data to provide more information and a “more nuanced and constructive” way to measure vulnerability.

The head of economic policy and small states at the Commonwealth, Travis Mitchell, also hails from the Caribbean. His team was responsible for devising the UVI, after what he called a comprehensive and objective look at what makes developing countries vulnerable.

Commonwealth officials made it clear that, while small states such as those in the Caribbean and the Pacific had been the models which launched the UVI work, the coronavirus pandemic had brought home the need to build back better for every nation and had shown how vulnerable anybody could become after an unforeseen disaster. [While developed countries started using the phrase in 2020, the Caribbean has been using the term “Build back better” since at least 2017.]

Baroness Scotland described small states as the canaries in the coal mine, suffering hurricanes, tsunamis and other climate crises over the years. Asked about the experience of the island of her birth, Lady Scotland said that by GDP, Dominica had been ranked as a middle-income country six hours before Tropical Storm Erika hit in 2015. Six hours later, it was a completely different economic story.

She added that the island’s economy had been “wiped out”, with damage from Hurricane Maria in 2017 costing more than 200% of Dominica’s GDP. Yet in the aftermath of that catastrophe, Dominica was still ranked as middle-income. Worse still, if a small state built up its infrastructure only to have it destroyed by a natural disaster, it was still left with the debt that it had incurred building that now-demolished infrastructure. Ultimately, its vulnerability had to be linked to its resilience and ability to build back afterwards.

Lady Scotland said GDP had worked as a measure 75 years ago following the Bretton Woods agreement, but it was not the best method today.

How the pandemic can help

Commonwealth officials hope that the pandemic has helped focus the minds of the rest of the world on the unexpected nature of disaster and the need for a more flexible way to link vulnerability and resilience. For the UVI team, the proposed index speaks to the reality of small states and the new reality of the rest of the post-Covid world.

“To respond as an international community, we must overhaul the way we think about development finance,” Baroness Scotland said. The world now needed to “create a better tool to understand vulnerability and respond to the resilience that is needed”.

Vaccine inequality

Questions also came up about vaccine inequality during the discussion on funding and debt inequality. The Commonwealth team said they had been taking part in the growing movement to get more coronavirus vaccines to the wider world. Baroness Scotland said the Commonwealth was working on a memorandum of understanding with the World Health Organisation to get more vaccines to help small states get up and running again. She said: “It is going to cost trillions of dollars in lost economic opportunities if countries are not given the vaccines they need.”

Highlighting the impact of the pandemic on tourism, fishing and other global industries, Travis Mitchell said that UVI would measure the contribution made by tourism to a country’s vulnerability. He pointed out that for the sake of tourism, countries did not just need the vaccine themselves but they also needed the wider world to be vaccinated. “This exposure paralyses them,” he added.

He added: “The world did not heed the evidence that has been given. Covid-19 has indicated that we do have to heed Mother Nature... This time is truly different.”

2018 and the year of Caribbean infrastructure

Building back better - Turning goodwill into strategy