Lost and Found: Digging up a more complicated historical narrative

By Debbie Ransome

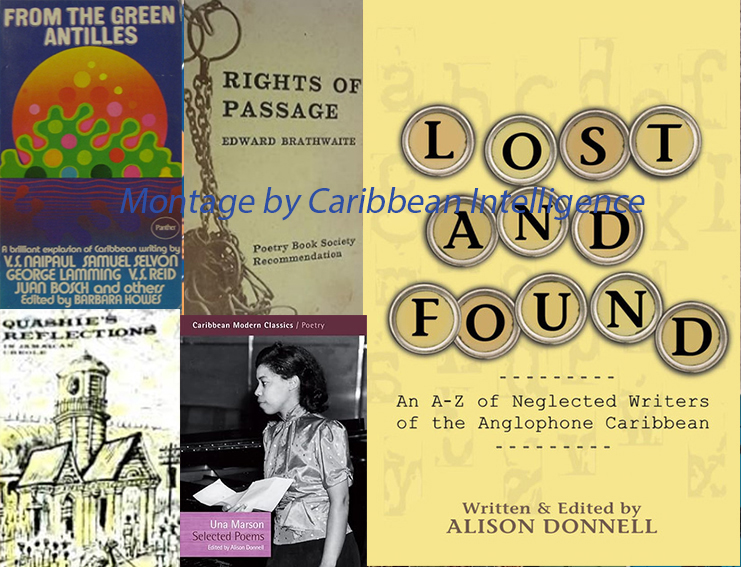

We all know the basic diaspora narrative: from slavery and indentureship to independence, the Windrush and other journeys. But here’s how to experience it afresh. The book Lost and Found: An A-Z of neglected writers of the Anglophone Caribbean, by Alison Donnell, is the product of more than 30 years spent delving into the works and actions of now mostly forgotten mid-century Caribbean wordsmiths.

It shines a light on the formation of the political parties that would steer their islands to independence. It also bestows belated attention on many talented Caribbean authors who moved back and forth between the then West Indies and the UK, chronicling the experiences of their peoples at home and abroad.

Some of the names that pop up in these biographies are known to many of us, including Una Marson and Henry Swanzi. The book demonstrates how they played an active part in academic, media and political circles. As their letters and diaries show, they helped shape the deliberations of those who assumed power in the post-independence landscape.

Another key figure is Jamaican-born Vera Zilla Alberta Taylor, who played an early role “at the heart” of the political grouping that would form the Jamaican People’s National Party (PNP). As Prof Donnell explains, her diary and her private correspondence with Edna Manley, whose husband Norman founded the PNP and became the country’s first premier, give an insider’s view of those aspirations in the 1940s.

Grenadian-born Eula Redhead found that her husband’s civil servant career allowed her to write and publish on her home island and in Barbados as she travelled with him during his regional career. She became so well known in Caribbean political circles that Barbados Prime Minister Errol Barrow asked her to compose a story for the Caribbean Heads of Government Meeting in Carriacou in 1960.

London calling

Although best known for her work at the BBC, Jamaican Una Marson receives credit in this book, not just for her impact showcasing Caribbean literary talent via the BBC and in her own Pioneer Press, but also for her own literary works. There is scrutiny of her plays and poetry, taking us way beyond her BBC career.

Prof Donnell charts the growth in public acknowledgement for Marson in the 21st Century, leading to a blue plaque at her former London home, a Google Doodle in 2021 and a 2022 TV documentary. The book states: “In many ways Marson’s writings have only come back into view because she has been championed as a feminist and nationalist, but ultimately aligning her work with these movements cannot do justice to the complex and competing cultural tensions to which she sought to give expression.”

The short biographies and summaries of the writers’ works also look at a lesser-known feature of West Indian life – the friends of the Caribbean, often born in the UK, who fought for emancipation and for local history, culture and language to be part of the curriculum.

Scottish-born Elma Napier (pen name Elizabeth Garner) is one such example. The eldest daughter of Sir William Gordon-Cumming, she “discovered Dominica” with her second husband in 1931 and they settled there. Napier went on to write novels set in her adopted island and became such a prominent political figure that in 1940, she was the first woman elected to Dominica’s Legislative Assembly. Her work encouraging co-operative efforts on the island led to her appearance on a Dominican stamp in 1973 to mark her national contribution.

Inez Knibb Sibley, who wrote under the name of Pennibb, was a white woman born in Jamaica who dared to write imagining the voices of African Jamaican figures. Prof Donnell points out how this “may nowadays be open to questions around cultural ventriloquism and appropriation”.

Knibb Sibley’s great-grandfather, William Knibb, a Baptist missionary and emancipationist, had been put under armed guard in 1831 during the so-called Baptist War, also known as the Sam Sharpe Rebellion, because he was seen as an ally to Africans enslaved in Jamaica. Knibb Sibley herself became a regular columnist for Jamaica’s Daily Gleaner and her writings were widely published and broadcast in the 1940s and 50s.

The book explains:

In terms of her writings, most of Sibley’s work is clearly directed at a Jamaican audience. In common with Skeete and Redhead, Sibley had a strong sense that Caribbean children needed to be conscious of their history and sensitised to their environment.

Her most recognised work Quashie’s Reflections was first published in 1939. When republished in 1968, it included a foreword by the then Vice-Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Sir Philip Sherlock.

This book is not only about island history. Zee Edgell is examined as “the only Belizean literary name known to scholars”. Her work Beka Lamb is described as detailing “the nationalist movement in British Honduras from the eyes of a teenage girl”.

Peter Kempadoo’s semi-biographical Guyana Boy, published under the name Lauchmonen, “documents life on a sugar estate and the experience of growing up on a plantation”. His Old Thom’s Harvest is described as reflecting “the religious, cultural and ethnic practices of rural families and communities in Guyana”.

The book finds a writer for every letter of the alphabet, sometimes playing with a pseudonym to complete the format. X is for still “unfound” mid-century writers – published but today unexplored in critical accounts.

With its short but informed vignettes on each of these writers, Alison Donnell manages to give the reader a sense of the mobility of the times. Writers move seamlessly around the Caribbean, to the UK and back, sharing their talents on the platforms available at the time. These included the BBC’s Caribbean Voices and Calling the West Indies, the Daily Gleaner, BIM Magazine (founded by Frank Collymore in 1942) and Public Opinion Magazine (1861-1951).

Prof Donnell has dug deep to speak to writers before they died and to their relatives later to tap into a lesser-known stream of West Indian talent. Without such research, such a line-up of Caribbean talent could have remained lost, never to be found again.

Debbie Ransome is the Managing Editor of Caribbean Intelligence and the former Head of BBC Caribbean.

Lost and Found: An A-Z of neglected writers of the Anglophone Caribbean by Alison Donnell, Papillote Press, 2025.

Look beyond the main streets and you can find political commentary, diverse culture, great people watching and a chance to make new friends